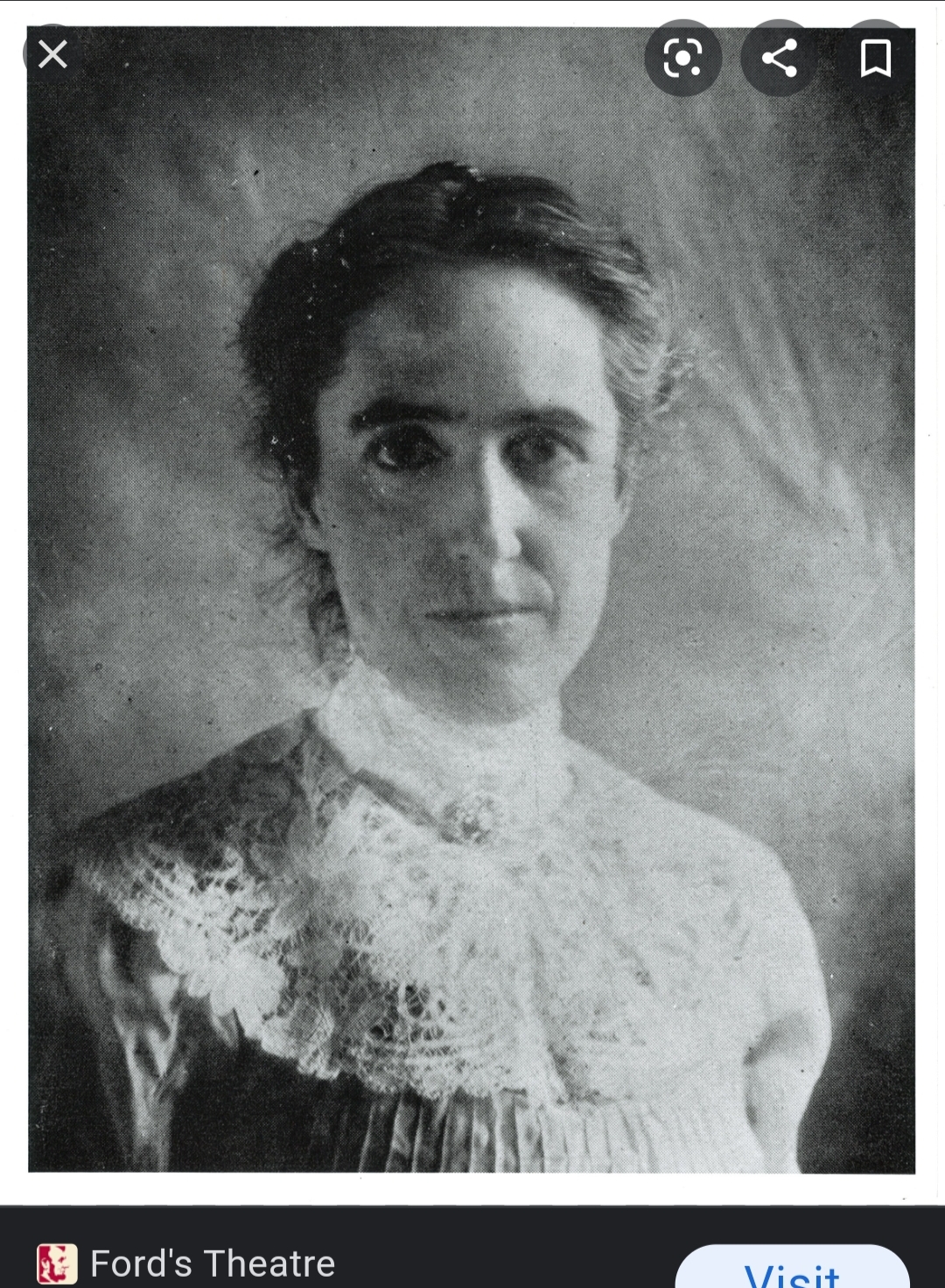

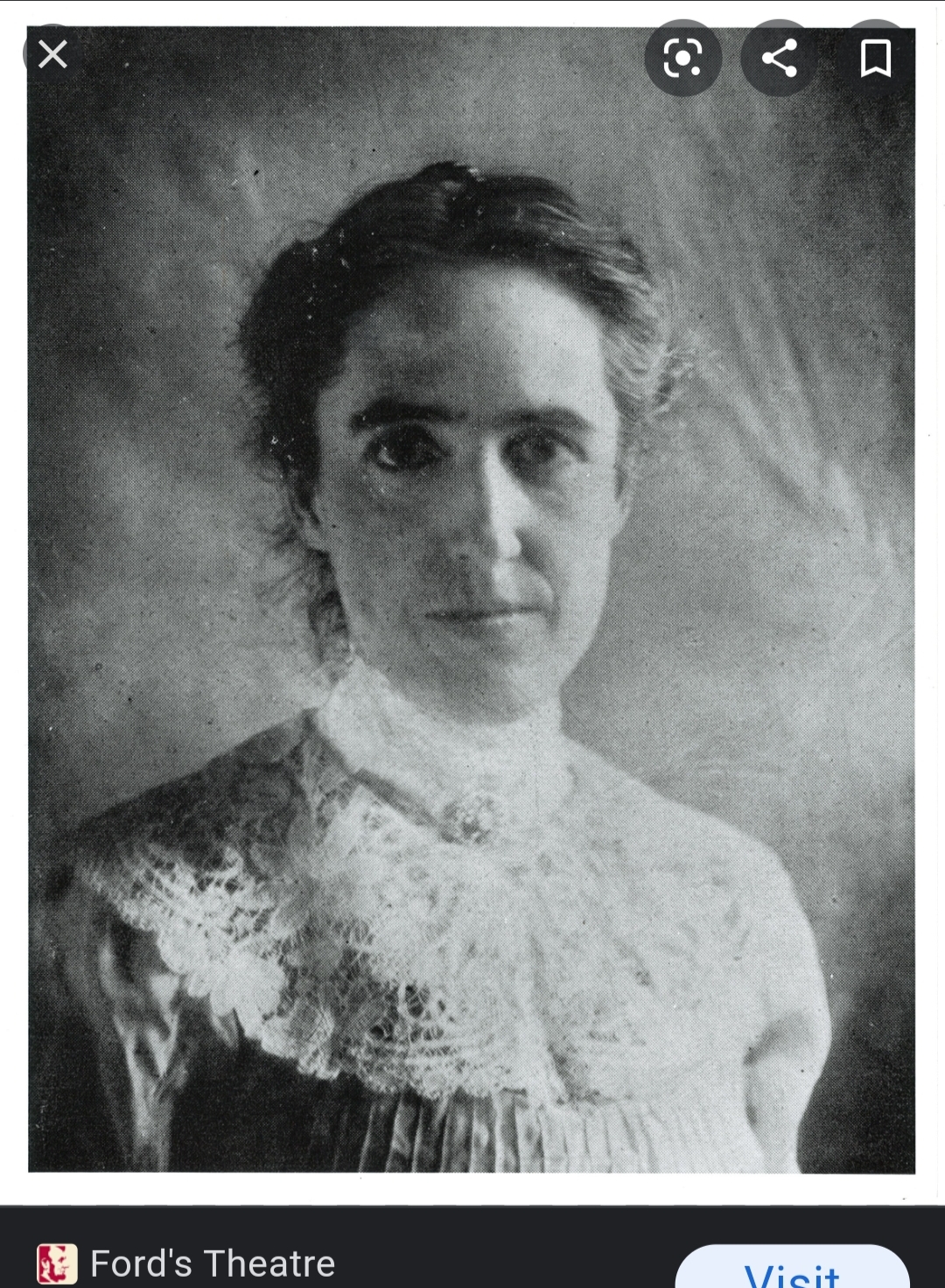

1022: Henrietta Swan Leavitt

The Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe

Born: 4 July 1868, Lancaster, Massachusetts, United States of America

Died: 12 December 1921, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America

She is most known for discovering the relation between Luminosity and Period in Cepheid Variables. Don’t worry if that makes no sense to you, I’ll try to explain it better in a minute.

Henrietta was one of seven children, two of whom died in infancy. She suffered from ill health throughout her relatively short life (she died when she was fifty-three), and Henrietta never married or had children of her own. She was devoutly religious; her father was a minister for the Congressional Church, and Henrietta kept up her faith throughout her life.

Henrietta studied at Oberlin College for two years before transferring to what would soon become Radcliffe College, where she graduated in 1892. Soon after, Henrietta fell ill and was left with permanent hearing damage as a result (she would slowly grow to become almost completely deaf over time) as well as suffering from eye issues and other illnesses. Henrietta never let any of this hold her back.

In 1895, Henrietta took on a position at the Harvard Observatory as a star cataloguer (in a purely voluntary position at first). She became a permanent staff member in 1902. While working at the observatory, Henrietta was employed alongside Williamina PS Fleming and Annie Jump Cannon.

Henrietta was so good at her job; she was promoted to Head of the Photographic Stellar Photometry department in 1907. Since all of this is way over my head, I’ll give credit to Henrietta’s Encyclopedic Britannica article who described her new position at the Observatory thusly:

A new phase of the work began in 1907 with Pickering’s ambitious plan to ascertain photographically standardized values for stellar magnitudes. The vastly increased accuracy permitted by photographic techniques, which unlike the subjective eye were not misled by the different colours of the stars, depended upon the establishment of a basic sequence of standard magnitudes for comparison. The problem was given to Leavitt, who began with a sequence of 46 stars in the vicinity of the north celestial pole. Devising new methods of analysis, she determined their magnitudes and then those of a much larger sample in the same region, extending the scale of standard brightnesses down to the 21st magnitude. These standards were published in 1912 and 1917.

She then established secondary standard sequences of from 15 to 22 reference stars in each of 48 selected “Harvard Standard Regions” of the sky, using photographs supplied by observatories around the world. Her North Polar Sequence was adopted for the Astrographic Map of the Sky, an international project undertaken in 1913, and by the time of her death she had completely determined magnitudes for stars in 108 areas of the sky. Her system remained in general use until improved technology made possible photoelectrical measurements of far greater accuracy.

Henrietta discovered around 2,400 variable stars (meaning they went from dim to bright and back quickly—and by quickly, I mean within a few days or weeks) which was half of all known variable stars until 1930, several years after her death. Her most important achievement came with her work of the aforementioned Cepheid Variables. Henrietta discovered that the period of time in which the Cepheid’s brightness changed was a regular period of time and determined by the star’s luminosity itself. This discovery led to author George Johnson (author of Mrs. Leavitt’s Stars) to describe Henrietta as “the woman who discovered how to measure the universe".

Henrietta’s work allowed for more well-known astronomers like Hubble and Shapley to determine distances between these Cepheid stars, as well as galaxies and clusters in which the Cepheids were observed.

In 1924, Edwin Hubble used Henrietta’s work to measure the distance to the great nebula located within Andromeda; the first time a distance was measured outside of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Sadly, according to one source Henrietta was not given proper credit for any of this work until many years later. In actuality, Professor Pickering, the man in charge of the Harvard Observatory, took credit for Henrietta’s work because she simply worked for him.

Henrietta worked at the Harvard Observatory until she died from cancer. According to one source, several years after her death, she was proposed for receiving a nomination for a Nobel Prize. Sadly, the Nobel is not awarded to those who have already died, and so the nomination never moved beyond the realm of possibility.

Badges Earned:

Find a Grave Marked

Located In My Personal Library:

The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars by Dava Sobel

Who Knew? Women in History by Sarah Herman

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henrietta-Swan-Leavitt

https://www.aavso.org/henrietta-leavitt-%E2%80%93-celebrating-forgotten-astronomer

https://www.famousscientists.org/henrietta-swan-leavitt/

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5852246/henrietta-swan-leavitt