"Whoever makes me unhappy for a day, I will make suffer a lifetime."

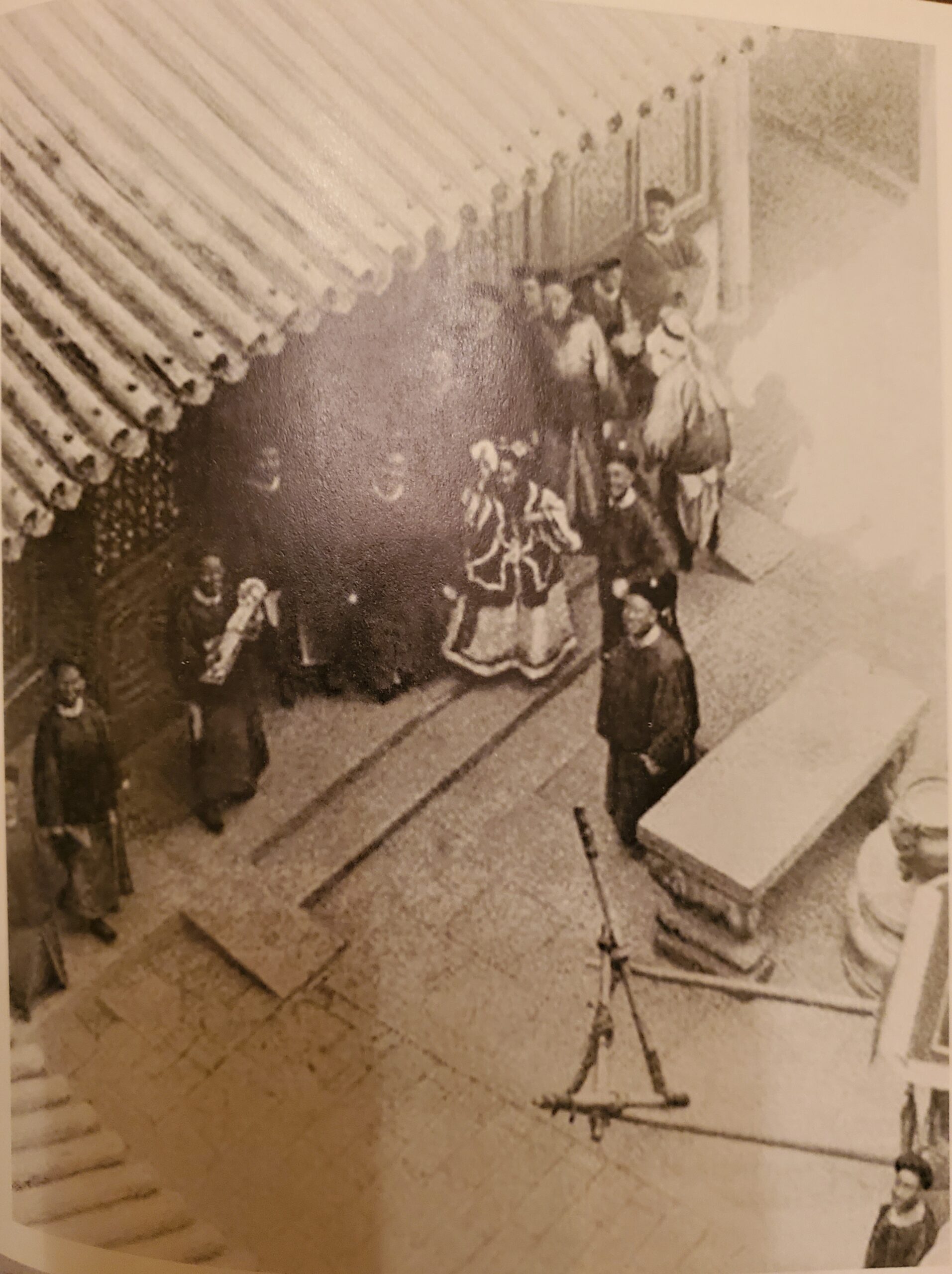

The Empress's triumphant return, photo sourced from Empress Dowager Cixi by Jung Chang

1016: Empress Dowager Cixi

The Empress who Dragged China into the Modern World

Born: 29 November 1835, Beijing, Imperial China (Present-day Beijing, People’s Republic of China)

Died: 15 November 1908, Zhongnanhai Imperial City, Imperial China (Present-day Zhongnanhai Imperial City, People's Republic of China)

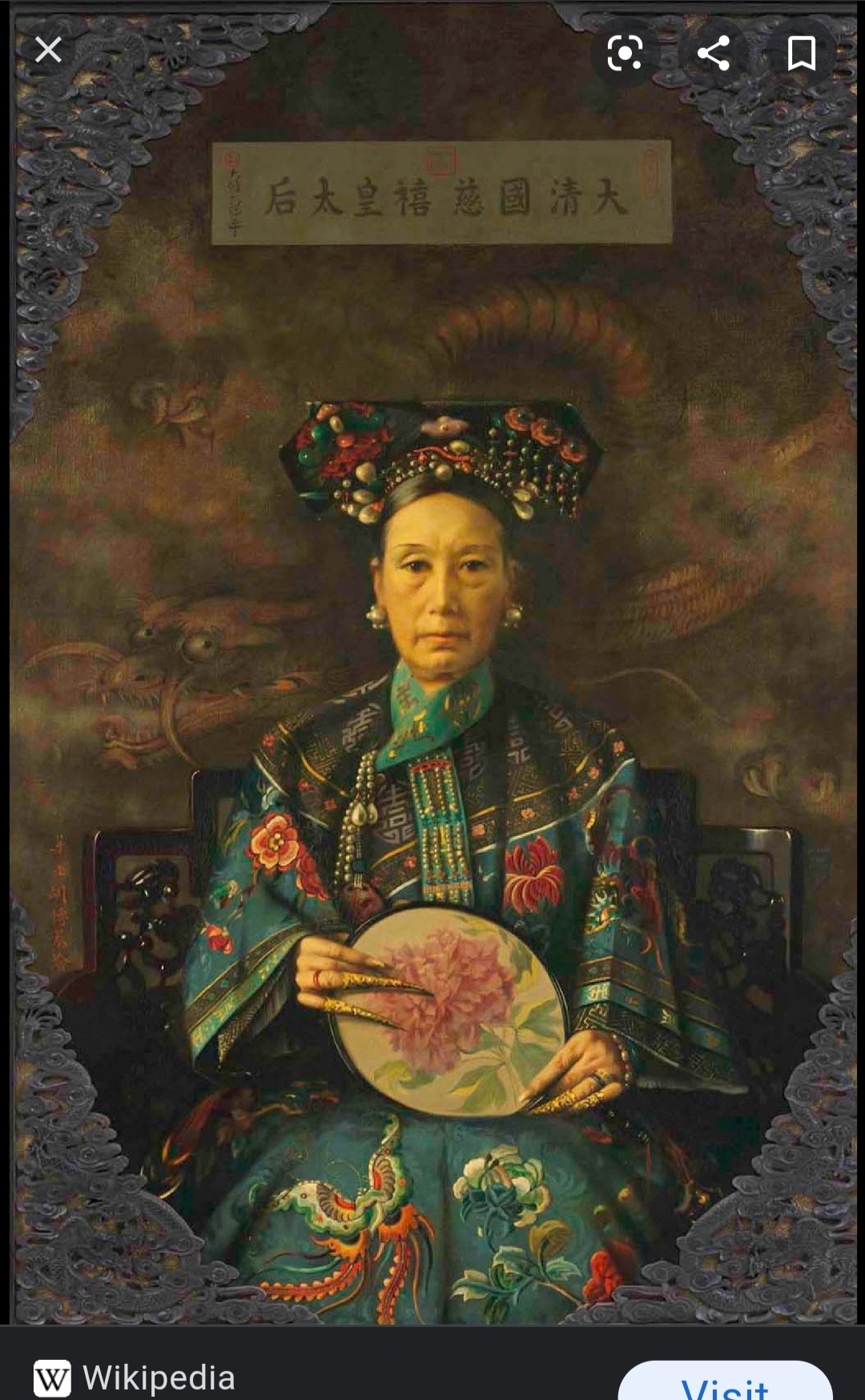

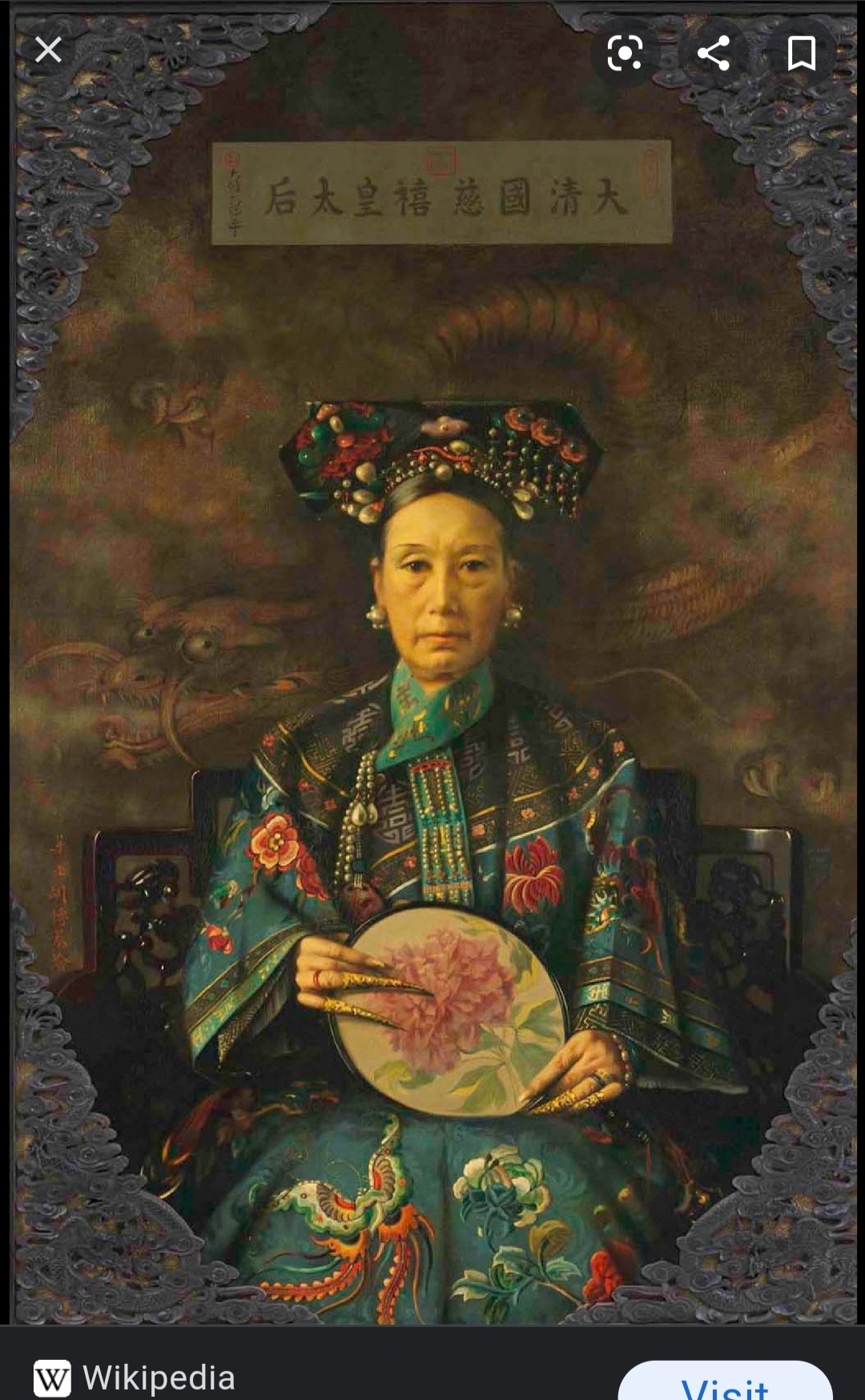

Cixi was the consort of Emperor Xianfeng, mother of Emperor Tongzhi, and adoptive mother of Emperor Guangxu.

Cixi ruled over the Manchu Imperial House of the Qing Dynasty.

Cixi was born into a wealthy family and was the oldest daughter. Unfortunately for her family, they were subject to a crippling tax by the Imperial government and struggled for many years because of it. Some historians even say Cixi’s father sought her advice and counsel to help the family through their harder periods. Cixi was only semi-literate, but this isn’t surprising given that A) she was a girl, and B) the Chinese language back then and today is one of the hardest in the world to learn to read and write. She wasn’t stupid by any means, but she was far from a renowned Confucian scholar.

Because she was Manchu, the ethnic minority, and not Han, the ethnic majority, Cixi did not have to bind her feet in the "traditional" lotus foot.

Today, Cixi’s birth name has been lost to history (though some sources like Smithsonian claim her birth name was Yehenara), but what we do know is that she was brought to the Forbidden City as a teenager (around the age of sixteen) and selected to be a member of the emperor’s harem. Cixi was not one of the higher-ranking concubines, and stayed near the bottom of the ladder until she gave birth to the Emperor’s son, Tongzhi.

When Cixi’s son was still a young child, the emperor, Xianfeng, died. Xianfeng’s short rule had been blighted by a series of worsening crises for Imperial China. First, he had to deal with the brutal Taiping Rebellion, which left a third of the country under rebel control. Then Xianfeng watched as Britain and France invaded his country as part of the Second Opium War. In short, Xianfeng’s reign was short, disastrous (though this was only partially his fault, to be fair), and his death left China in an even bigger mess than he had first found it when he became emperor a decade before.

Before the emperor’s death, he had written up a will in which he stated for a select group of eight men from the court to rule over the country on behalf of his five-year-old son, until Tongzhi could reach his majority and rule in his own right.

By the time Xianfeng died, Cixi had become friends with Empress Zhen (also spelled Ci’an). In the Chinese imperial court system, one of the women selected for the harem was chosen to serve as the Emperor’s wife and Empress. In Xianfeng’s case, that woman was Zhen. Zhen had one daughter but no biological son. However, the Chinese Imperial system dictated that Cixi’s son, Tongzhi, was legally the empress’s son and not Cixi’s, despite the fact that Cixi had given birth to the child.

With Xianfeng dead, Cixi and Zhen decided they didn’t want to be forced into an early retirement. They also didn’t trust the group of men the emperor had selected to rule the empire on his son’s behalf. Working together, Cixi and Zhen managed to convince the court that the two of them should rule as equal ranking Empress Dowagers, serving as regent for Tongzhi until he was old enough to rule in his own right. They did this with the help and support of two of Xianfeng’s brothers, Prince Gong (who wanted to appease the west and stop the war), and Chun, who had married one of Cixi’s younger sisters.

Once Cixi and Zhen were in control, they ordered one of the eight men to be executed and two others to commit suicide. The other five men went free. With their power secure, Cixi changed her name (she had previously taken on the name Yi when entering court life) to Cixi “kindly and joyous” while Zhen changed her name to Ci’an “kindly and serene.” Today, most historians refer to the second Empress Dowager as either Zhen or Ci’an, somewhat interchangeably, and I will continue to use Zhen to try and make this less confusing to those of you reading this who aren’t ultra-familiar with Chinese history.

Cixi would rule imperial China, almost uninterrupted, from 1861 to 1908. Today, most people recognize the United Kingdom’s Queen Victoria (By the way, between 1861 and 1901, the two female rulers, Victoria and Cixi, effectively governed half of the world—now that’s a fun fact!) and remember Victoria's long reign, so why is the same not true for Empress Dowager Cixi, who also ruled for decades and managed to use her power for mostly good? Its true that Cixi never ruled in her own right. That title falls solely to Empress Wu Zetian, who ruled China on her own over one thousand years before Cixi. But even though Cixi always ruled as either regent or co-ruler alongside a man (first her biological son Tongzhi, and then her adopted son Guangxu), she still managed to oversee China’s modernization, from a sleepy farming society to a technological powerhouse.

Cixi is most widely credited with helping modernize China by bringing in the first railroad (though she took twenty years to finish building the line because she didn’t want to interrupt the countryside in which ancestral tombs had been built) and instituting electricity amongst other achievements. Cixi was also cautious however. She opposed the building of textile factories because she worried they would take jobs away from women who had been doing jobs by hand for centuries. Cixi also managed to oversee the creation of China’s first modern navy, helped stabilize the economy and eliminate the Taiping Rebels once and for all.

Two of the major shakeups from her reign to be noted were the decrees of 1902, which legalized marriages between Han and Manchu and also banned the foot binding practice which had been going on for centuries. Another improvement was the 1906 announcement that Cixi would make China a constitutional monarchy with elections. Unfortunately, her dream did not survive long, but more on that later.

Because Cixi suffered from the unfortunate birth defect of having two X chromosomes, she had to rule a bit differently than a man. For one thing, Cixi was never allowed to enter the entire front section of the imperial palace structure, aka the Forbidden City. She always had to enter through the back half of the complex and never set foot in the front portion, which was reserved for the Emperor. For another thing, Cixi had to speak with her ministers from behind a screen. Men were not allowed to see the Empresses (Cixi and Zhen, when Zhen was still around), and so for the vast majority of her reign, Cixi spoke from behind a screen and the ministers had to reply through that same screen.

In 1873, Tongzhi came of age and began to rule as emperor in his own right. By then, Empress Zhen and Cixi were forced into retirement, just like they’d been trying to avoid when Xianfeng died. However, two years later, Tongzhi died from smallpox. He had left no heir, and his empress, Xiaozheyi, was encouraged to starve herself to death by her birth family (I wish I was kidding about that).

With Tongzhi dead, the Empire was in crisis mode. Cixi decided to kill two birds with one stone, and swept back into power as Empress Dowager, serving as regent to her newly adopted son, Guangxu. Who was Guangxu? Oh, the three-year-old son of her sister and brother-in-law, Prince Chun. Remember him from earlier? In the years since Chun had helped Cixi secure power, he had turned against her for different political reasons. Now, Cixi took away his eldest son and forced him to retire, because Chun could not serve in the government of which his own son was the new Emperor. Think of it as a conflict-of-interest type thing. In any case, Cixi was back, the future of the dynasty was (hopefully) secure, and things could get back on track after the two-year lapse of nothing happening because Tongzhi couldn’t be bothered to actually rule most of the time.

A few years after Guangxu ascended the throne, Empress Zhen died. Zhen’s death was a serious blow to Cixi, who had come to view Zhen like a sister, an equal partner. With Zhen gone, Cixi was left with the sole reigns of power over Guangxu, who was still an impressionable child at the time. Unfortunately, the cracks in their relationship had already started to show by then. Zhen was usually able to bring Cixi and Guangxu back together after a time, but with her dead, Cixi and Guangxu were headed down a path of irreconcilable differences.

In 1889, Guangxu took over as sole ruler of China. Once again, Cixi was pushed back into retirement. However, Guangxu had been raised to be the perfect Confucian scholar, and this meant he opposed any and all things western, including most of Cixi’s modernization efforts. In 1895, after Guangxu had allowed the navy to slip into a shell of its former self, the empire was soundly defeated in a war with Japan. The crisis reached a point that the government and court brought Cixi back, knowing if they had any chance of living another day, they needed her wisdom and wit to save the empire.

Cixi retained control even after the crisis averted, and the tension between her and Guangxu continued to grow worse and worse. In 1898, a plot was uncovered to assassinate Cixi. The plot involved the emperor. If this knowledge came to the public forefront, the empire could be ruined. Guangxu was placed under house arrest, and ruled simply as a puppet while Cixi controlled the strings.

In 1901, Cixi and Guangxu were forced to flee the Forbidden City with the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion. For over a year, Cixi ruled from a safe house outside Beijing. Once the Boxers were repelled, she returned to the Forbidden City triumphant. An iconic photo of Cixi dates from this time. A man on a rooftop shouted down to her. Cixi turned around and waved to the camera in one of the few, if not the only, photograph of her smiling. Cixi was an old woman by then, but she was still a bada** to say the least.

After her triumphant return, Cixi put into place the aforementioned reforms like allowing inter-ethnic marriages, banning foot binding, installing China’s first telegraph, and announcing China would become a constitutional monarchy, like the United Kingdom. Cixi also allowed for an expanded freedom of the Chinese press, something that would have been unheard of only a decade before. Cixi also fought to end brutal torture methods like Lingchi—death by a thousand cuts. Going even further, in 1907, the year before she died, Cixi also fought and saw the issuance of a decree that mandated women receive an education. This meant Chinese women saw scholarships to travel abroad to earn a higher degree for the first time, and other women were able to be educated at home thanks to multiple schools being opened across the country.

Despite all this success, Cixi was aware of her age, and knew the end was near. Guangxu had failed to have a legitimate heir in the years since becoming the emperor, meaning the throne had no clear path forward.

For obvious reasons, Cixi did not trust Guangxu or his ability to govern with her gone. Recent scientific studies have proven Cixi had him poisoned when she felt her own end approaching. Cixi died one day after Guangxu. Only one more emperor would rule after Cixi and Guangxu (Cixi’s grand-nephew), before he was forced to abdicate (the Emperor, named Puyi, was a child at the time and his mother and regent, Empress Longyu, signed the abdication documents), ending imperial China once and for all.

In 1928, Cixi’s tomb was bombed and damaged by the Kuomintang Army. Members of the army also stormed the tomb, tore open her sarcophagus, and pulled jewels off of Cixi’s corpse, including a large pearl from between her teeth. In 1949, the tomb was restored by the Communist government, and is a tourist attraction today. I highly doubt Cixi would have approved of the CCP, and not just because they turned her final resting place into a tourist trap.

Badges Earned:

Find a Grave Marked

Located In My Personal Library:

Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine who Launched Modern China by Jung Chang

Bad Days in History by Michael Farquhar

American Goddess at the Rape of Nanking: The Courage of Minnie Vautrin by Hua-Ling Hu

The Only Woman by Immy Humes

Pirate Women: The Princesses, Prostitutes, and Privateers Who Ruled the Seven Seas by Laura Sook Duncombe

Sources:

Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine who Launched Modern China by Jung Chang

https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/snapshot/cixi-last-empress-dowager-china

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/cixi-the-woman-behind-the-throne-22312071/

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/china-history/empress-cixi-facts.htm

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/28149843/empress-dowager-cixi