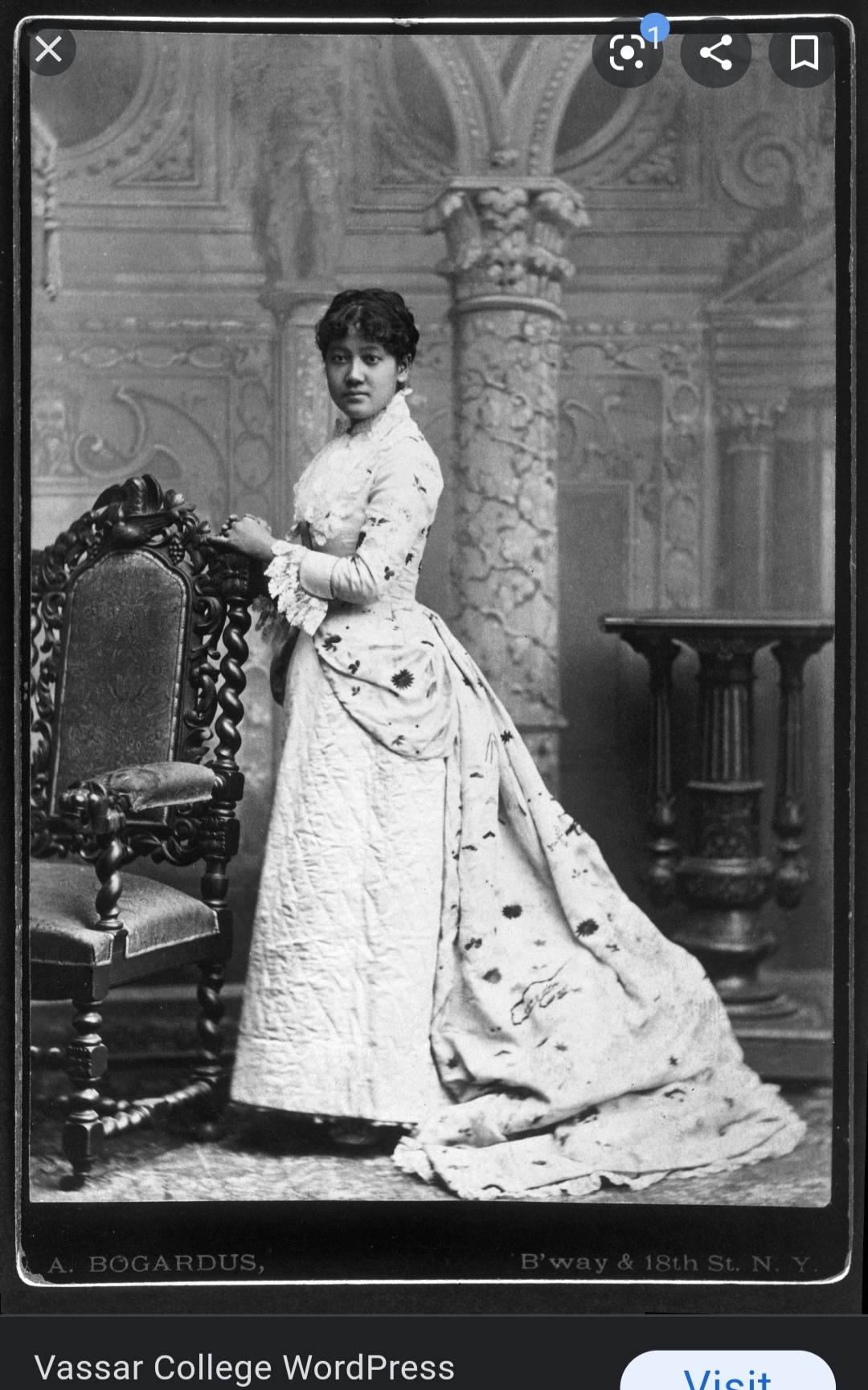

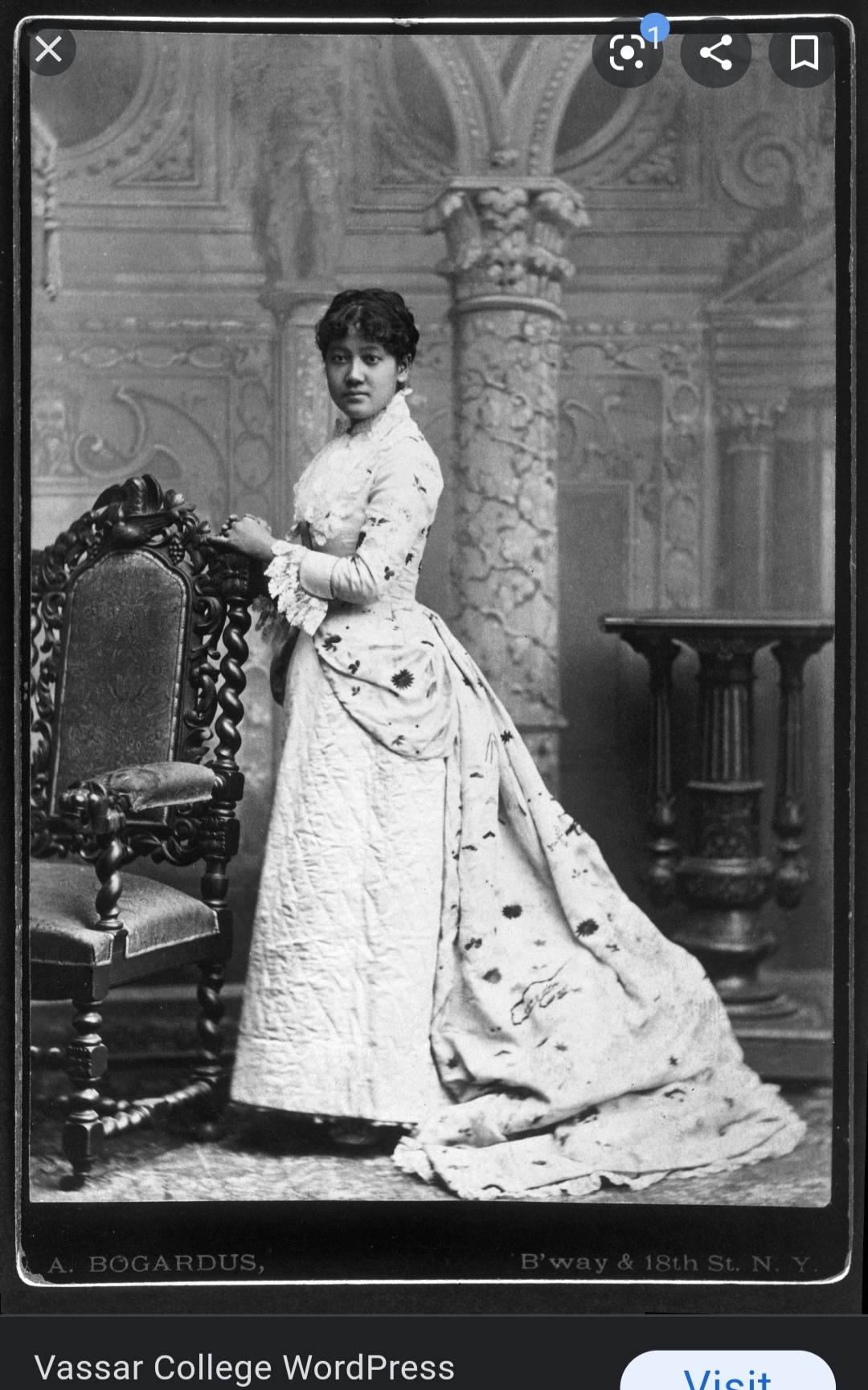

1054: Sutematsu Ōyama

The First Japanese Woman to Earn a College Degree From a Western College

Born: 16 March 1860, Present-day Aizu, Japan

Died: 18 February 1919, Tokyo, Japan

Also Known As: Princess Ōyama

Original Name: Sakiko Yamakawa

Unfortunately for Sutematsu, attending college wasn’t actually her choice. Her family forced her to go. She was eleven years old when she left her home to go abroad for her higher education. Sutematsu was one of five girls selected for the educational mission that was meant to last ten years. At the time, Sutematsu did not know a word of English, and must have been terrified by the very prospect.

Sutematsu’s family were descended from the samurai, and Sutematsu’s generation was the last to remember the elite warrior class before the war that ended the Samurais supremacy throughout Japan. When Sutematsu was only eight years old, the war reached her hometown of Aizu. Even though she was still just a child, according to Rejected Princesses, Sutematsu would provide additional ammunition to the gunners within the city and might have even smothered landed shells with wet quilts in order to prevent them from exploding. On one such occasion, the shell burst before Sutematsu’s sister could smother it in time. The shrapnel given off from the shell would kill Sutematsu’s sister-in-law and leave her with a large scar on her neck from where she herself had been struck.

According to Vassar College’s biography of her:

Sutematsu’s selection for [the mission to attend college abroad] was curious, considering her family’s relationship to the emperor of Japan. She came from a samurai family who were vassals to the Prince of Aizu, one of the last to surrender to imperial forces in the mid-nineteenth century civil war which ended the shogun’s reign and restored the emperor to power. In 1868, eight-year-old Sutematsu and her family were involved in the siege of Wakamatsu, during which the women and children supported the war effort from within the castle while the men battled the imperial warriors outside the castle walls. Sutematsu’s future husband, General Oyama, who was part of the imperial forces during that battle, later liked to joke that the shell that hit him during that battle was made by Sutematsu herself.

Of the five girls sent to the United States, two went home after only a few months because of the stress of the new country and culture. After a few months in the country, the remaining three girls, including Sutematsu, had hardly learned more than a word of English. The three girls were then separated and sent to different foster homes, making them feel truly alone in the world.

At Sutematsu’s new foster home, her family renamed her “Stemats” because they couldn’t pronounce her full name. She was sent to public school and soon began to excel in her classes. After her high school graduation, she became the only girl to go on to college.

Sutematsu graduated from Vassar College in 1882. Her sophomore year she served as president of her class, and she also became a member of the prestigious Shakespeare Club. By the time she returned home to Japan after graduation, she had lost her fluency in literature in the Japanese language, but she was proficient in English and able to write correspondence in French.

Sutematsu married after realizing there were few professional opportunities for women in Japan. She then had three children of her own as well as helping to raise three from her husband’s first marriage. She served as a volunteer nurse for the Japanese Red Cross during the Russo-Japanese War.

Eventually, Sutematsu became the most educated Japanese woman alive. She later opened the Peeresses School for noblewomen and fought for the education rights of girls of all classes after teaming up with the other two girls she had been originally sent abroad with. Working at the school was extremely hard work, and Sutematsu found herself being pulled further and further away from normal Japanese society. She was too Anglicized for her own people, too Japanese for the Americans, to much of a feminist for the Conservatives in her country, and too close to the Empress for those on the more democratically thinking side of the political aisle. Around this time, Sutematsu wrote a letter to her American foster sister stating, “My husband grows fatter every year, and I thinner.”

Finally, in 1899, the Japanese government mandated at least one school for girls be created in each prefecture in the country. Soon after, Sutematsu helped one of the other girls who had gone to America with her by funding a school her old traveling companion had built. It was the first college opened for anyone who wanted to attend in the country.

In 1919, a flu epidemic landed in Tokyo. Sutematsu decided against fleeing the city. She instead stayed behind the ensure the school stayed open. Only a few weeks later, she died from the disease less than a month before her fifty-ninth birthday.

Badges Earned:

Rejected Princess

Located In My Personal Library:

Daughters of the Samurai: A Journey From East to West by Janice P Nimura

Tough Mothers by Jason Porath

Sources:

http://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/alumni/princess-oyama.html

https://specialcollections.vassar.edu/collections/manuscripts/findingaids/oyama_sutematsu.html

https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/princesses/sutematsu-oyama